Please find a copy of the speech given by Dr Mamphela Ramphele at the Stellenbosch University Faculty of Theology open day on the 2nd of February 2015.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

We are privileged to be able to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of one of South Africa’s finest sons, Beyers Naude, born on 10th May 1915. It is fitting that his alma mater has honoured him by amongst others, namingthe Centre for Theology after him and organizing this Annual Lecture to reflecton Theology and Public life.

Beyers lived his life as a spiritualsearcher for “the truth“. The search for“the truth” during the dark days of apartheid brought him face to face with thechoice between obedience in faith to God or subjection to the authority of thechurch’s doctrines. The Dutch ReformedChurch’s doctrines of the time were heavily tainted by chauvinist and racistideology that supported and promoted the socio-economic exclusion of blackcitizens. This doctrine undermined the pillarson which humanity stands – the fundamental truth that all humans are created asequals in the image of God. Beyers Naude chose obedience to God and paid theprice of social disapproval and exclusion by the Afrikaner establishment.

Today is an opportune moment for us toreflect on our own journeys as people of faith. We need to examine the extent to which we have made the kind of choicesthat affirm our faith in the equality of humans and commitment to building asociety characterized by Ubuntu – thehuman connectedness that binds us together as equal members of the human race. Ubunturequires us to confront the legacy of socio-economic and political exclusion ofblack people by a white power structure. The persistence of Poverty, Unemployment andInequality is a result of our failure to establish the human connectedness thatis essential to making Ubuntu a way oflife. We are yet to see ourselves inthe faces our fellow human beings made in the image of the God we worship.

Our Theme: Confronting Poverty,Unemployment and Inequality gives us an opportunity from a Theology andPublic Life perspective to reflect on the texts of great thinkers about this brokennessin the human connectedness in our society. It is also an opportunity for us to recommit to healing ourselves asindividuals, our communities and our society as a whole. In this lecture I would like to reflect onthree points:

1) Thatthe process of Confronting Poverty, Unemployment and Inequality is inextricablylinked to the restoration of the moral health of individuals and the health ofour political community.

2) Thetough choices that Spiritual Leadership faces in responding to the call topromote the structural transformation that is fundamental to uprooting Poverty,Unemployment and Inequality.

3) Theneed to nurture the Green Shoots of a new Struggle for True Liberty

CONFRONTING POVERTY, UNEMPLOYMENT ANDINEQUALITY

Our society is struggling to come to termswith the essential structural transformation that is required to build thecountry we committed to establish to make freedom a reality in the daily livesof all citizens. The growing poverty, persistentunemployment and yawning chasm of inequality are symptoms of a society withdeep wounds and excruciating social pain for those on the wrong side of thedivide. The euphoria of 1994 blinded usto the reality of the extent of transformation and healing needed to build thenon-racial, non-sexist and just democratic society envisaged in ourconstitution.

We need to confront and dismantle thesocial structures, that enabled a minority to exploit a majority of ourpopulation, that remain intact to date. For example our cities remainsegregated. Dormitory townships are supporting the prosperity and comfort ofthe well to do areas with their labour, consumer spending and taxes. Take the case of staple food items such asbread. A recent analysis shows that atownship such as Soweto with approximately 2million poor and unemployed people spendabout R10m per day on sugar-laced bread amounting to R3.65bn per year. All that money leaves Soweto and billionsmore from other townships. Ultimately leaves South Africa as repatriatedprofits of multinational bread companies. This economic model can only generatepoverty for the majority and super wealth for the minority that owns most ofthe capital in our economy.

Our education and training systems stillchurn out poor quality outcomes for the majority of children and young people.This leaves them ill-prepared to seize the labour market and self-employment opportunitiesin our economy. The productivity of oureconomy suffers from the poor quality human capital. The humiliation of life in poverty in themidst of conspicuous consumption is a source of re-traumatization, a disabling senseof worthlessness, anger and frustration. The social instability, brutality of violence and extent ofself-sabotage in those dormitory townships are a direct result of thestructural violence the society visits upon them daily. This violence and social instability willincreasingly spill into well to do areas of our towns and cities.

The celebrated Indian Economist, C.T.Kurien, laments the pursuit of wealth at the expense of those excluded andexploited. He urges the global communityto confront the traditional economic model. He is concerned about the reduction of humanachievement to monetary achievement. In virtually every field from technologyto spirituality success is increasingly measured in terms of a monetary number.The relentless pursuit of these numbers has taken its toll on social processeseven as it has led to the over exploitation of natural resources without even apassing thought to the needs of future generations. He defines poverty as “the carcassthat remained from wealth acquisition.” SampieTerreblanche brings this concern closer to our own situation: “In South Africa we can regard (black)poverty as the carcass left over from (white) acquisition.”[1]

Inequality generated by this economicmodel and the disrespect that goes with it, adds salt to the wounds of thosewho have to endure its burdens. Thesocial fractures occasioned by the triple burden of poverty, unemployment andinequality undermine our connectedness as a human community.

What are we to do to contribute to theprocess of structural transformation that is essential to healing the socialpain and wounds of our society as people of faith and citizens and peopleobedient to God in Faith? I am encouraged in this exploration by the congruencebetween the views of St. Augustine, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Dag Hammarskjold andRabbi Jonathan Sacks on the freedom we have as human beings to choose how tolive as creatures designed for connectedness with other humans. Allthese thinkers link human freedom to action in the service of others.

Augustinians place a strong focus on sinas “attempts to flee from other humans,and also from God, (as) the really fundamental characteristic of what sin is. It(sin) is an attempt to treat others as objects so that we do not have toconfront what it would be like to treat them as humans and be exposed to theirclaims upon us as humans.”[2]

Both Bonhoeffer and Hammarskjold (who werecontemporaries born in different parts of Europe) define sin asself-centeredness – to be curved in upononeself. Freedom in their view isinseparable from unreserved service. Freedom “is a freedom in the midstof action, and the action required is the action to serve others.”[3] For both of them the life of aChristian is that of one who lives and acts in the midst of the needs of theworld.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks in his wisereflections on Freewill had this to say: "Whenlife becomes cheap and people are seen as a means to an end, when the worstexcesses are excused in the name of tradition and rulers have absolute power,then conscience is eroded and freedom lost because culture has createdinsulated space in which the cry of the oppressed can no longer be heard."[4]

The exclusionarysocial structures of the apartheid exploitative system designed to create “insulated space in which the cry of theoppressed could not be heard”, sadly remain intact to date. Many of us living in the leafy suburbs ofmajor towns and cities can not, and do not, and will not hear the cry of thosestill living with unspeakable pain of poverty, unemployment and inequality. We flee – physically and symbolically fromthe places where we would have to confront the claims that our fellow humansmake on us as a connected human race.

Not unlike “the pre-conversion” BeyersNaude, we have found it difficult to challenge the establishment, because weare of it. Those in government authorityand in leadership positions in the private sector are part of us. We are a part of networks of support andpatronage that operate amongst those seen to be loyal to the political andeconomic establishment.

Many of us as people of faith have foundourselves caught in the horns of a dilemma. How to be supportive of a newgovernment led by struggle heroes, whilst being obedient to God in faith and beingon the side of those crying under the burden of persistent injustices in theirdaily lives? How do we remain true to ourobedience to God in faith in a society that seems to have come to tolerate continuedpoverty, unemployment and growing inequality? How do we challenge impunity in public life by the very people alongside whom we fought against the impunity of the apartheid system? How long is long enough to begin to demandaccountability in public life as non-negotiable?

Beyers Naude, as a member of the AfrikanerBroederbond, faced the same dilemma when it became obvious to him that theAfrikaner establishment was committing atrocities such as the Sharpeville Massacre,and the systematic denial of the human dignity of his fellow citizens simplybecause they were black. He too was toldto be patient by his friends, the likes of Rev Bertie Brink, who said: “Brother Beyers, I just want to advise youthat it is going to take years and years before our church realizes thatapartheid cannot be spiritually justified. Therefore, we must be patient.”[5]

In our midst today are also peoplecounseling patience. There are thosesuggesting that 20 years is too soon to expect transformation to have the desiredimpact on the lives of people living in poverty, unemployment and suffering thepain and indignity of inequality. Many others are saying that 20 years is toolong for those children who still do not get the high quality early childhooddevelopment they need to lay the foundations for success in life. More and more are saying that 20 years is toolong for those cohorts of young people – black and poor - 50% and more of whomdrop out of our school system due to poor quality teaching and learning intheir foundation years.

Young people are saying that 20 years istoo long for those who against all odds, make it into the minority who qualifyfrom high school, yet end up without opportunities for higher education andskills training to prepare them for successful careers in the 21stcentury. A growing chorus says that 20years is too long for the thousands of women and children who die unnecessarilyin childbirth due to poor quality health services despite the science andresources we have to stop the carnage.

Like Beyers Naude, we face the choicebetween obeying God’s call to us to respond to the demands of our fellow humanbeings to make true liberty visible in our society or continuing with thestatus quo. We are challenged to admitthat true liberty is not divisible – we cannot be free when the majority of ourfellow human beings remain un-free. Wehave to tackle both the structural and psychological impediments to connectingthe moral health of individuals and the health of our political community withthe goal of true liberty for all. Wehave to accept that a corrupted polity will effectively corrupt its citizens,and corrupted citizens will effectively corrupt their polity.

We have made the big mistake ofjettisoning the psychological dimension of the struggle for true liberty in1994. People who have been deeplywounded by decades of humiliation by political and socio-economic exclusion,cannot simply stand up and dust themselves up and move on. The superiority and inferiority complexes ofracism and sexism, as well as the assault on the culture and self-image ofblack people, have left a multiplicity of deep wounds to heal on theirown. A healing process is needed toacknowledge the wounds, apply the balm of truth speaking between perpetratorsand victims, and dismantle the structures that continue to wound millions ofblack people.

Reconciliation can only come from puttingright that which has gone wrong (structural transformation). As citizens and as Faith Based Leaders wewere too hasty to declare victory, especially after the Truth and ReconciliationCommission (TRC) process in the late 1990s. We left too many wounded people, who are the majority population, totheir own devices by excluding socio-economic violations of human rights fromthe TRC process. We have also not followed through with the minimalist reparationsproposed in the TRC Report.

What is needed is a new business model forour economy. We need to rethink andtransform the socio-economic structures of our cities to stop the haemorragingof cash from the poorest to the wealthiest parts of our urban landscapes. We need to address the cost of poverty in transportcosts, time away from families and lack of leisure and other facilitiesessential to enhancing the quality of life for poor people. We need to advocatefor, and champion larger investments in quality public services to enhance theoutcomes of education and health for all citizens.

We also need to be open to innovations inpower generation technologies that focus on renewables and new human settlementmodels that integrate residential and industrial/commercial productiveactivities. Our economy can only growfaster and in a more sustainable way by adopting models that promote the utilizationof the talents and energies of all able bodied people willing to participate inbuilding ours into a great society.

We need to dismantle our “insulatedspaces” and be present in the lives of those wrestling with the triple burdenin our midst. We need to listen to thecry of those black people plunged into self-hatred because of the dailyhumiliation and denigration they continue to endure. We need to understand that destructivebehavior including self-sabotage, in personal, community and public life of ournation, is a direct result of the psychological liberation work yet to be done.

Too many white people remain burdened by asuperiority complex that distances them from their fellow human beings. There are too many white people who stilljustify the legacy of privilege they continue to enjoy as an entitlementresulting from their superior education, skills and harder work. There are still too many men who believe thatthey are entitled to lead rather than recognize the complementary strengthswomen bring to leadership.

Beyers Naude, as founder and head of theChristian Institute, was one of the first white people in the 1970s torecognize the importance of psychological liberation through raising the consciousnessof both black and white people about the impact of racism and socio-economicexclusion on human relationships. Beyershad benefitted from Afrikaners consciousness raising and solidarity action toheal the psychological wounds of humiliation Afrikaners suffered at the handsof the British. He supported the BlackCommunity Programs (BPC was the development arm of the BCM) to model practicalmanifestations of self-reliance to drive black led sustainable developmentprojects.

The gap left by the neglect of psychologicalliberation has been filled by, amongst others, the new churches. Theyoffer salvation for those suffering the pain of being in the margins of society. Some of these new churches, despite theirlimited human and material resources, are answering the call to hear the cry ofpain by being present in the daily struggles of poor people.

But many of these new churches aremega-businesses with global links to centers in the USA and SouthernAmerica. They offer a prosperity ministrybased on transactional relationships involving significant financialcontributions and unquestioning obedience to the authority of church leaders. The level of desperation and loss ofself-esteem of the congregants involved is reflected by the extent to whichthey engage in further humiliating acts such as eating grass, drinking petrolor slavish submission to abusive church leaders. How do we stop the sin of fleeing from theclaims these desperate fellow humans are making on us as humans?

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF LEADINGSTRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATION

Dag Hammaskjold’s life of public serviceas Secretary General of the United Nations in the Cold War era of the 1960s, isan inspiration we might draw on in this exploration of our own healing journeysas we confront the challenges and opportunities of structural transformation ofour society. Hammarskjold’s life of publicservice was anchored on the search for life’s meaning. This search led Dag to conclude that the wayby which one finds life meaningful is the way of experience; one seeks meaningby “daring to take the leap intounconditional obedience you will find that ‘in the pattern’ you are liberatedfrom the need to live ‘with the herd’. You will find that thus subordinated, your life will receive from Lifeall its meaning, irrespective of the conditions given you for its realization”.[6]

The liberation from ‘the need to live with the herd’ and enjoyment of the benefits ofbeing a member of the Afrikaner Broederbond, is what enabled Beyers Naude toleap into “unconditional obedience”to God. The question for us today is howwe are to liberate ourselves from ‘the needto live in the herd’ and commit ourselves to tackling the structural andpsychological obstacles to true freedom for all South Africans? The church at various stages in its life,including during the struggle for freedom from apartheid, anchored its missionon the connection between the moral health of individuals and the health of ourpolitical community.

Imagine if people of all faiths were tomake 2015 the year of breaking down the edifice of socio-economic structuresthat perpetuate poverty, unemployment and inequality in the contexts we livein! People of Faith across the religiousspectrum have historically been involved in advocacy for social justice and as actorsin socio-economic development projects, especially education and health care. What stops the church today from respondingto the desperate needs for quality education, health care and promoting humandignity in our homes and communities?

There are inspirational stories emergingfrom across our country of citizens doing extraordinary things with limitedresources. Take the example of civicengagement of retired people in Hermanus, in the Western Cape, who havecommitted themselves to transforming the local schools in the poor township ofZwelihle into high quality places of teaching and learning. Enhancing education quality is transformingthe mindsets of those involved on both sides of the divide. It sets the stage for dismantling the dividesin Hermanus between masters and servants, opening the gate towards rebuilding asociety of equal citizens.

Other citizens in Gauteng and Mpumalanga aresimilarly helping to make excellence affordable to poor communities through lowcost private schools. Forgingpartnerships between poor public schools and better-resourced schools, is alsoworking wonders in enhancing performance across the board. These are not, and should not be acts ofcharity. These are citizen responses to building a society we can all be proudto live in.

Imagine if citizens of Stellenbosch wereto step outside their comfort zones to support the push for quality educationfor every child in settlements on your doorstep such Khayamandi! The knock-on effects would includecollaboration between the very high net-worth residents and the poor people ofKhayamandi. Together they would build a re-connected healing community ofStellenbosch, where human dignity is celebrated at home, at work and in thewider community. The same amazing thingscould happen if Cape Town leafy suburban citizens would dare to reconnect withtheir fellow humans on the Cape Flats.

The over-60s in our society are anunder-utilized resource. Theis resource could be harnessed to tackle structuralconstraints to sustainable socio-economic development. Many citizens in this age group have a wealthof experience, scarce skills and independent financial means. Imagine connecting our huge youth base – thelargest proportion of our population (59%) under 35 years – with the almost 10%of our population who are retired and still energetic! The enthusiasm and energy of youth inspiredand nurtured by mutually supportive relationships with older generations couldbecome a winning proposition for our society.

The linking of hands to innovate andexperiment with new business models to accelerate economic growth, educationand training as well as job creation, could see us turning round our moribundeconomy into a thriving one. We could turnthe challenges of the triple burden into an opportunity to build bridgesconnecting us as fellow human beings. Becomingmore attentive to the needs of our fellow human beings and learning from oneanother, are the ingredients needed to build a more prosperous, inclusive and stablegreat country together.

GREEN SHOOTS OF A NEW STRUGGLE FOR LIBERTYFOR ALL?

There are encouraging signs across ourcountry that people of faith are waking up to their responsibilities andrecommitting to obedience to God in faith. First, many individuals are openly searching again for appropriateresponses to the growing social justice challenges in our midst. The courage to engage in a new struggle onthe side of poor people is being championed by a growing number of faith-basedleaders.

The South African Council of Churches(SACC), that played a seminal role in proclaiming liberation theology andsupport for the struggle for freedom, is being revived after years ofneglect. Leaders such as Rev FrankChikane, Bishop Malusi Mpumlwana, Ms. Hlope Bam, have stepped up to the role ofgiving the SACC revival a boost. Here inthe Western Cape The Religious Leaders Forum led by Rev Xola Skosana is gearingup for a stronger prophetic voice and greater responsiveness to the cry ofthose living on the margins of our society.

The Methodist Church of Southern Africa has also taken a bold step by putting a stop to its priests acting as Chaplainsto the ANC. The Chaplaincy of the ANChad become controversial in its support of the ANC’s claim to “being of God”and therefore deserving support from God-fearing citizens.

The Archbishop of Cape Town, ThaboMakgoba, has also come out in support of actively standing with thosemarginalized by poverty and indignity. Hehas called for 2015 to be a year of “renaissanceof the spirit and the reconnection with the values of our constitution and ourspiritually guided families …… You have the chance to shape our country’sdestiny. Destiny is not a matter ofchance, but a matter of choice.”[7]

There are other encouraging initiativesafoot as well. The Authentic HopefulAction (AHA) had a soft launch in December 2014 to mobilize action against thetriple burden of poverty, unemployment and inequality. It draws its strengths from the Second KairosInitiative that presented an open letter to the ANC leadership in 2012,challenging the persistent social injustice and growing corruption ingovernment. The success of AHA willdepend on its ability to ignite the imagination and energy of citizens and thefaithful to mobilize a sustainable social movement for a new struggle forsocial justice.

The successful sprouting and blossoming ofthese green shoots depends on the extent to which they inspire citizens acrossthe spectrum to rise to the challenge and opportunity of building a movementfocused on uprooting poverty, tackling unemployment and inequality. The question for you and I here today is howwe respond to the call to obedience as we go back to our bases? Are we ready to ”take the leap of obedience” and start the process of dismantlingthe socio-economic barriers we have built in our own lives or those weperpetuate to insulate ourselves from our fellow human beings? Are we ready for the journey to reconnectwith our fellow human beings?

CONCLUSION

Let me conclude by bringing in the voicesof young men from Khayelitsha whom we seldom have the opportunity to listen to. They are part of a group supported by aninitiative by two traditional ballet dancers that enabled them to escape theclutches of gangs to rebuild their lives They are exceptional in theirperformance as dancers moving gracefully in a celebration of ballet and Africandancing motifs. The untapped talentamongst these young people is immeasurable. Let me share with you the lyrics of a song they composed during oneevening during a weekend away organized by their mentors:

Ndiyoyika

Ndiyabuza kaloku, yini

na sibulalana sodwa

Bayaphi ubuntu

Sesisele sisodwa

simunamunana nak’ilahle

baphi na abadala

ndiyabuza kaloku.

Sifuna wena Mama nawetata

Uyabanda umzi ongena

mfazi

Kwanele ma-Africa

Kwanele bantwana

Bo’mtonyama

Masibambaneni

I’m afraid

I’m asking why are we

killing each other, where

is our humanity

We have been left alone

Trying to find answers

Where are the elders

I’m asking

We want our mother

and father

A house with no woman

is cold

It’s enough my fellow

Africans

It’s enough sons and

daughters of the soil

Let’s unite

How are we to respond to these voices? We have the power, theresources, the experience and models of success, to root out poverty,unemployment and inequality. The keyquestion is whether we are willing to make the choice to respond and expressour obedience to God through service to these young people and others in ourmidst so we can restore our human connectedness.

Mamphela Ramphele

Active Citizen

2/2/2015

[1] C.T. Kurien, Wealthand Illfare — An Expedition into RealLife Economics, Books forChange, 139, Richmond Road, Bangalore-560025. Rs. 390. Terreblanche, S. AHistory of Inequality in SA: 1652-2002, University of Natal Press, 2002p413.

[2] A Conversations With CharlesMathewes, Ass Professor of Theology at the University of Virginia andauthor of A Theology of Public Life, Cambridge, USA, 2007, Boisi Centrefor Religion and American Public Life, Boston College, USA.

[3] Dag Hammarskjold’s White Book – An Analysis of Markings,p129, Gustaf Aulen, 1969, Fortress Press.

[4] Rabbi Jonathan Sacks,Covenant and Conversations 5775 one Ethics, Freewill

[5] Beyers Naude, My Land vanHoop, Human and Rousseau, 1995:43

[6] Dag Hammaskjold, Markings, p114, as quoted in An Analysisof Markings , Gustaf Aulen, p35, Fortress Press 1969.

[7] Time for a New Struggle,Archbishop of Cape Town, Thabo Makgoba, Sunday Independent, 11/1/2015

Tuesday, December 13, 2022 at 10:06AM

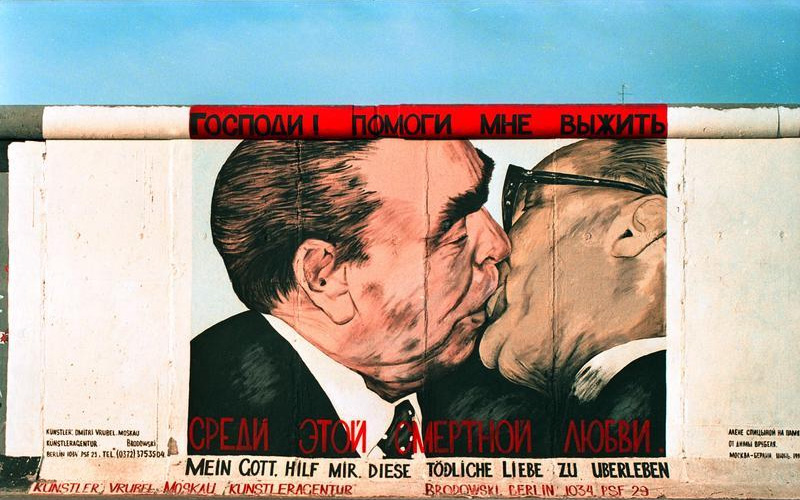

Tuesday, December 13, 2022 at 10:06AM  I love Berlin! It is an amazing city. I have been here many times in the last decade. As I write this, I am sitting in my office in the Theology Faculty at the Humboldt University Berlin, looking out over the Spree river towards the Berliner Dom (Lutheran Cathedral) and Museum Island. I am here on an extended stay as part of a research sabbatical. But, of course, there is another side to contemporary Berlin. It is a city whose residents challenge convention and push the boundaries. Graffiti is a common sight as are some rather interesting fashion choices.

I love Berlin! It is an amazing city. I have been here many times in the last decade. As I write this, I am sitting in my office in the Theology Faculty at the Humboldt University Berlin, looking out over the Spree river towards the Berliner Dom (Lutheran Cathedral) and Museum Island. I am here on an extended stay as part of a research sabbatical. But, of course, there is another side to contemporary Berlin. It is a city whose residents challenge convention and push the boundaries. Graffiti is a common sight as are some rather interesting fashion choices.